New ways to treat skin conditions which affect millions of people could be on the way after a scientific discovery.

New ways to treat skin conditions which affect millions of people could be on the way after a scientific discovery.

Experts led by the University of Dundee have discovered the gene which causes dry skin, leading to eczema and asthma.

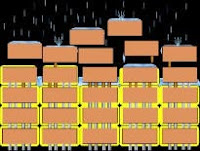

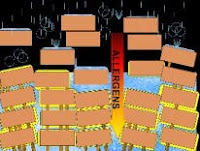

The gene produces the protein filaggrin, which helps the skin form a protective outer barrier.

Experts hope to use the discovery for more effective therapies to tackle the root causes of the conditions, rather than simply treating the symptoms.

At the moment the only treatment is through the use of emollients and ointments or anti-inflammatory drugs.

"If you imagine the disease as a burning building, up until now we've just been throwing buckets of water on the roof" - Prof McLean, University of Dundee

The research, to be published in the journal Nature Genetics, was undertaken with collaborators in Glasgow, Dublin, Seattle and Copenhagen.

Filaggrin, abundant in the outermost layers of the skin, keeps bacteria and viruses out while keeping water in to prevent the skin from drying.

Reduction or absence of the protein leads to dry and flaky skin.

Professor Irwin McLean, of Dundee University's human genetics department, said the elusive gene had been known about for 20 years or more but was difficult to analyse.

'New era'"It was a really tough project, but because we had experience in this type of gene, we managed to crack it where others had failed," he said.

"We see this as the dawn of a new era in the understanding and treatment of eczema and the type of asthma that goes with eczema as well.

"If you imagine the disease as a burning building, up until now we've just been throwing buckets of water on the roof.

"I was constantly at the hospital every day getting bandages from head to toe" - Jade Williamson, Chronic eczema sufferer

"But now we know exactly where the fire is underneath and we can put the hoses in there and hopefully tackle the cause of the problem properly."

Experts said new treatments from the discovery could take some time to come to fruition.

Jade Williamson, from Rosyth in Fife, said the discovery could lead to her having a complete life for the first time.

The 22-year-old fitness student developed what was first thought to be nappy rash when she was six months old, but the condition later grew into chronic eczema.

She said: "I was constantly at the hospital every day getting bandages from head to toe.

"All you could see was my eyes, my nose and my mouth. It was distressing when I was younger."

Gene mutationMs Williamson said the problem sometimes became stressful when she was younger, adding: "When my skin was bad I did tend to close myself in my room and stay away."

She said that living with the condition brought a constant regime of moisturising and washing.

The study, which also involved Our Lady's Hospital for Sick Children in Dublin, showed that about 10% of Europeans carry a mutation that switches off the filaggrin gene, causing a very common dry, scaly skin condition known as ichthyosis vulgaris.

About five million people in the UK alone make only half of the normal amount of filaggrin protein and have a milder form of the condition, while 120,000 people in the UK have no filaggrin protein and often require specialist treatment.

More than one million people are predicted to have the severe form of the condition worldwide.

Source and copyright: http://bbc.co.uk

Information on natural eczema cream to soothe dry and flaky skin

.gif)